Accounts of deceit and exploitation within the music business have long involved accounts of artists being manipulated by their managers. Although the glamour of rock stardom might seem like a lifetime of incentive, numerous musicians are deceived by those they trusted to lead their careers. From classic rock bands to modern pop sensations, numerous performers have been mistreated by managers intent on “lining their own purses”, with all almost bankrupting their clients and in some cases, ruining their careers.

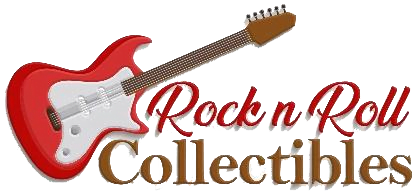

Lou Pearlman and the Backstreet Boys

One of the most well-known figures in music management, Lou Pearlman was known for creating several of the greatest boy bands of the 1990’s and early 2000’s. Bands such as the Backstreet Boys and NSYNC were the cream of the crop. However, behind the scenes, Pearlman was executing one of the largest monetary heists in pop music history.

Despite becoming the best-selling boy band of all time, with record sales over 130 million, the Backstreet Boys received hardly anything in royalties. The financial windfall achieved through their tours and merchandise sales, were taken by Pearlman, who had crafted a contract which paid him a ridiculous proportion of the group’s earnings. They did not uncover the scope of Pearlman’s ploy until years into their careers. Following this success, Pearlman was introduced to NSYNC, which was formed by Chris Kirkpatrick. Pearlman funded and managed NSYNC in a very similar fashion, selling over 70 million records globally.

With these two major successes under his belt, Pearlman was on his way to becoming a music mogul. Other boy bands managed by Pearlman were O-Town (created during the ABC–MTV reality television series Making the Band), LFO, Take 5, Natural, Marshall Dyllon (co-created with country music artist Kenny Rogers) and US5, as well as the girl groups Solid HarmoniE and Innosense, co-managed with Lynn Harless (the mother of NSYNC band member Justin Timberlake). Other artists on the Trans Continental label included Aaron Carter, Jordan Knight, Smilez & Southstar and C-Note.

With the exceptions of US5 and Marshall Dyllon, all the musical acts that worked with Pearlman sued him in federal court for misrepresentation and fraud. Backstreet Boys’ dissatisfaction began when member Brian Littrell hired a lawyer to determine why the group had received only $300,000 for all of their work while Pearlman and his record label had made millions. Fellow boy band NSYNC was having similar issues with Pearlman, and its members soon followed suit. All cases against Pearlman either have been won by those who have brought lawsuits against him or have been settled out of court.

Pearlman continued to con people with various other scams. It was eventually discovered that Pearlman operated a Ponzi scheme and then cheated his investors and bands. He was sentenced to prison for his financial rip-offs in 2008 and died there in 2016. Pearlman betrayal remains one of the most publicized instances of exactly how easily artists may be ripped off by all those they trust.

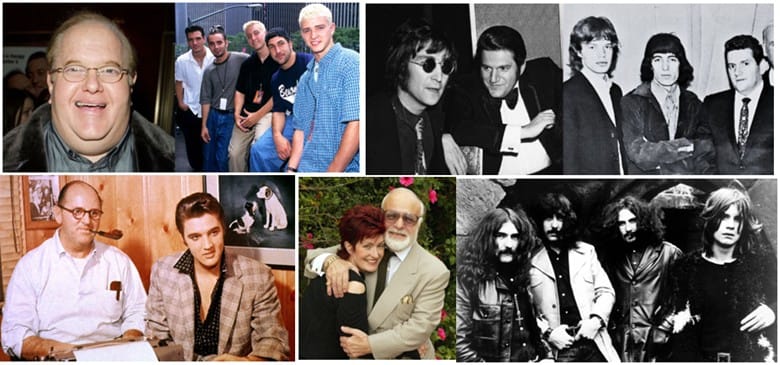

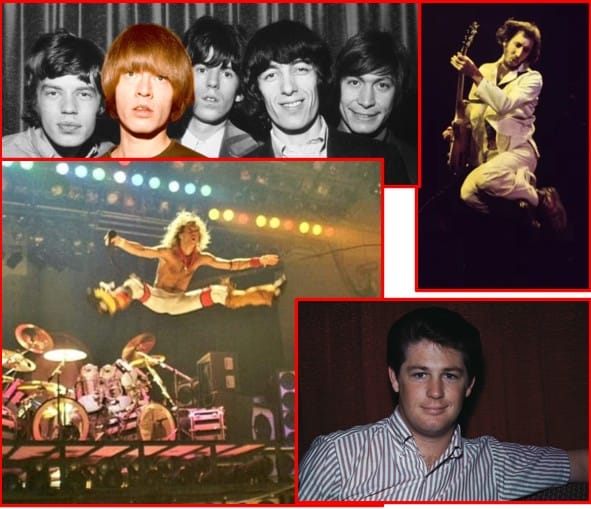

Allen Klein and The Rolling Stones

Parlaying his success with artists Buddy Knox and Sam Cooke into management deals with The Rolling Stones and The Beatles, Allen Klein set up what he called “buy/sell agreements” where a company that Klein owned became an intermediary between his client and the record label. This company owned the rights to the music, manufacturing the records, selling them to the record label, and paying royalties and cash advances to the client. Although Klein greatly increased his clients’ incomes, he also enriched himself, most times without his clients’ knowledge. For example, The Rolling Stones’ $1.25 million advance from the Decca Records label in 1965 was deposited into a company that Klein had established. The fine print of the contract did not require Klein to release it for 20 years. Klein’s involvement with both the Beatles and the Rolling Stones would lead to years of litigation. In 1971 the Stones sued Klein over U.S. publishing rights. The suit was settled the following year, with the Stones receiving $1.2 million as a settlement of all U.S. royalties earned up to that point (essentially the $1.25 million advance that Decca had paid the Stones in 1965 that Klein had been withholding since August 1965). But the Stones were unable to break their contract with Klein, who held an additional $2 million of their money to be paid over a 15-year period, ostensibly for tax purposes. Klein’s company, ABKCO, continued to control the rights to publish the Stones’ music and Klein made a fortune off the band’s all-time best-selling album, Hot Rocks 1964–1971.

Lawsuits continued back and forth throughout the ‘70’s and 80’s with the Stones being awarded 1.375 million in two different settlements and Klein maintaining control of all songs prior to the 1971 breakup. Starting in 1986, when the introduction of compact discs brought great profits to the music industry, relations began to improve between Klein and the Stones. In 2002, the Stones’ album Forty Licks and the Licks Tour, celebrating the band’s 40th anniversary, incorporated songs owned by ABKCO. The Stones agreed to a five-year payment plan suggested by Klein’s son, Jody. In 2003, Klein negotiated with Steve Jobs to make ABKCO’s Rolling Stones songs available on iTunes.

Similar but not exactly the same scenarios followed with his management of The Beatles. Over time, first in March 1971, Paul McCartney left his control and two years later, the other three members followed suit, with John Lennon stating, “Let’s say possibly Paul’s suspicions were right …”

Klein continued to be a major force in the music of these two groups, as he was never totally shut out. Klein left behind a legacy of financial manipulation not just for The Rolling Stones but The Beatles as well, causing similar royalties and financial control disputes.

Don Arden (and Others) and Black Sabbath

Don Arden developed a track record as being a rock manager through ruthlessness and intimidation. He managed the careers of rock acts such as Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, Gene Vincent, Air Supply, Small Faces, The Move, Black Sabbath, Electric Light Orchestra, and Trickster.

Unfortunately, he gained a reputation in Britain for his aggressive, sometimes illegal business tactics, which led to his being called “Mr. Big” or the “Al Capone of Pop”. A classic example of this behaviour came in 1966 when Arden and a squad of underlings turned up at impresario Robert Stigwood’s office to “teach him a lesson” for daring to discuss a change of management with Small Faces. Arden reportedly threatened to throw Stigwood out of the window if he ever interfered with his business again.

From 1976 to 1979, Black Sabbath were among the most prominent bands managed by Arden. Arden business practices, cut into the band’s income and he ruled with an iron fist – the band could not leave or even challenge him. Black Sabbath drummer Bill Ward recalls how easy it was for he and his bandmates’ management to steal from them at the beginning of their career. “We were taken for a ride financially,” Ward told Louder Sound in a new conversation around the 50th anniversary of Sabbath’s Paranoid album. “We couldn’t afford a lawyer. I was busy looking at the women’s backsides and everybody was drinking cognac, so it was all fine by me. It was only a few years after Paranoid that we started asking, ‘Er, where’s all the accounting?'”

Problems with management plagued Black Sabbath through several managers and most of its prime years. The title of Sabbath’s sixth album, Sabotage, was even inspired by its legal fight with one ex-manager, Patrick Meehan. An artist getting ripped off by a crooked manager was nothing novel in the ’70s, but for Ward and Black Sabbath, they’ve stayed wary after all these years.

Ozzy Osbourne along with his bandmates later admitted to being monetarily abused during their finest years. Arden’s command over the band’s career and income harmed their financial status and they struggled to recover from the mismanagement for a long time.

In an ironic twist Ozzy would later marry Arden’s daughter Sharon, who turned into his manager. Sharon ultimately split with her dad, accusing him of unethical practices and focused on protecting Ozzy from further exploitation.

Colonel Tom Parker and Elvis Presley

Colonel Tom Parker’s management of Elvis Presley is among the most famous and controversial instances of artist exploitation. Parker helped turn Elvis into an international superstar, but his manipulation of contractual details was incredibly suspect. Colonel Tom was dedicated to the money he could pump out of Elvis and Elvis’s success was a by-product of that process, not the other way around.

His merchandising alone grossed over $22 million by the end of 1957. It was arguably the first marketing campaign aimed squarely at the teen demographic. Parker initially took a 25 percent commission, which would have been on his actual concerts and record deals. This fee grew to 50 percent so that ultimately the Colonel made more off the toys, TV appearances and acting roles than Elvis.

Though he did not allow overseas tours, this was not for Elvis’ benefit. As someone who basically did nothing to thwart Presley’s growing dependence on drugs, it is not to be believe that his health was at the core for that decision. It is widely believed that his reason was due to his illegal immigrant status. He was afraid that international travel would produce some some border inspection questions about his murky passport history.

Starting in 1969 and ending in 1976, Elvis would play a residency of four to six weeks in Las Vegas.

In March 1975, during one of these Las Vegas visits, Presley along with Parker met with Barbra Streisand and Jon Peters. They discussed the possibility of Presley co-starring with Streisand in a remake of the film A Star Is Born. Seeing this as a chance to finally be taken seriously as an actor, Presley agreed to take the role if the contracts could be worked out. According to Presley’s friend, Jerry Schilling, Presley was excited about the opportunity to take on a new challenge. Streisand’s production company, First Artists, offered Presley a salary of $500,000 and 10% of the profits. Parker, who had always dealt with Presley’s film contracts, viewed the offer as a starting bid and asked for a salary of $1 million, 50% of the profits, plus another $100,000 for expenses. He also mentioned that they would need to arrange details of a soundtrack deal. First Artists, not used to such huge demands, didn’t put forward a counteroffer and decided instead to offer the role, along with the original salary offer, to Kris Kristofferson, who accepted.

Despite the huge income garnered by his exploitation of Elvis, the Colonel was not good with money and was no master dealmaker. He sold the rights to Presley’s early recordings for a relative pittance, gave away the rights to the master recordings and lost royalties after he negotiated Elvis’ seven-year contract with RCA Records in 1973. On a personal front, he squandered his own fortune due to his gambling habit.

Parker continued his management role until Presley’s death in 1977, and managed the Presley estate for several more years until the extent of his scheming came fully to light. In 1980, a judge ordered an investigation into his practices and found Parker’s management was unethical and that he likely cost Elvis (and himself) millions. Subsequent lawsuits left the Colonel estranged from the estate, despite some appearances at Graceland events, due to the invitations from Priscillia. Parker’s final years were spent living in Las Vegas, in declining health, until his death in 1997.

The stories of these managers highlight how the music industry is often both lucrative and shady. Though managers are critical in leading an artist’s career, excessive power and greed can have damaging effects, both emotionally and financially, on the artists who rely on them. The lesson for musicians is financial oversight, legal protection and watching who controls their career. However, that is much easier said than done, as the young artists normally have no concept of how to orchestrate their early years. Unfortunately, as history has shown, even the biggest stars can get ripped off by the ones they trust to do that.